“People Are Rewarded by Close Looking” – Kathan Brown of Crown Point Press on the Enduring Excitement of Printmaking

By Sarah Evers • May, 2019

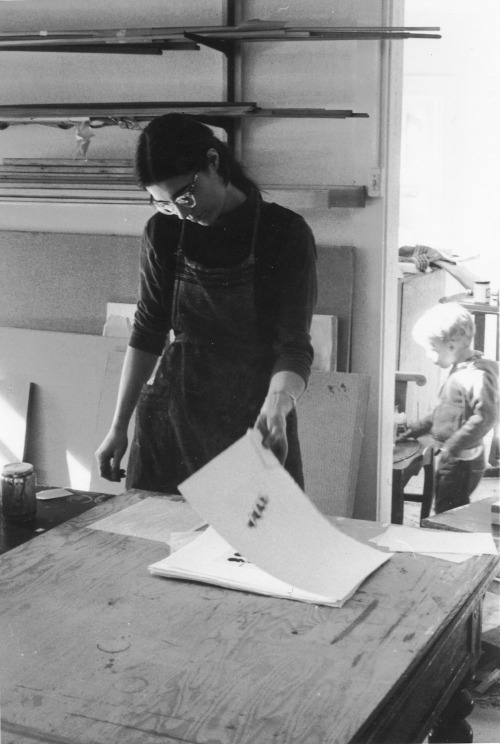

Photo by Laurie Fraenkel.

Crown Point Press is not your typical gallery; not often do you find an entire printing operation in the same venue as a dynamic exhibition space. Kathan Brown, a pioneer of printmaking in the San Francisco Bay Area, started Crown Point Press in 1962 in a storefront in Richmond, California. Moving to Berkeley and then Oakland in the early years, and settling in San Francisco in 1986, Crown Point began by printing and publishing Bay Area artists including Richard Diebenkorn, Beth Van Hoesen, Wayne Thiebaud, and Robert Bechtle. From 1971 through 1976, Brown and her printers also produced artist projects for New York publisher Parasol Press, which sent Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Dorothea Rockburne, and other East Coast artists to work at Crown Point.

What began as a studio focusing on the production of etchings has now expanded to the Crown Point Press of today: a renowned etching studio that is also an authority on printmaking and an important presence in San Francisco’s expanding gallery scene. Crown Point’s location around the corner from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is one reason why visitors to the gallery come from around the world, but the reputations of its artists and the importance of the books it publishes are a stronger factor. A passion for teaching others about the etching process is an essential component of Crown Point’s operations and makes the press stand out from a traditional gallery model.

The underlying message behind all Crown Point’s operations is the importance of printmaking, especially etching, along with a passion for keeping the art form alive. Its how-to books on hand-printing processes enable artists anywhere to have successful access. Videos of artists working at the press are available online, so anyone can witness the intricacies of the work. Crown Point Press also hosts summer workshops in which people across a spectrum of experiences can try their hands at etching.

We spoke to Brown about opening her own business, her relationships with local artists, the expansion of the workshop into a gallery, and more.

When did you first become interested in visual art?

I come from an art family. My mother went to the Art Institute of Chicago, and was a practicing artist all her life. She never stopped doing watercolors and drawings, even though it was not easy during the Depression when she was working full-time. My father was a professional photographer and we had a darkroom in our house. I made drawings and paintings with my mother and helped my father develop photographs in our basement. Art was all around me when I was young.

How did you originally become interested in etching?

I studied at Antioch College, which was not known as an art school but had a very good liberal education and was experimental back in the days when most colleges weren’t. When I told my art professor I was going to take a year off to study in London, he offered to get me into the Central School of Art. I said, “I’m not an art major,” and he said, “You should be.” He was persuasive. After a year abroad, I came back to graduate from Antioch with a major in art, and after graduation I returned to London for a second year at Central.

At the end of my second year in London I visited Edinburgh and discovered a dismantled etching press in the backyard of the rooming house where I was staying. The landlady said that students had brought it there to save it from being melted down for scrap during the war. “If you want it, you can take it,” she said. I had a plane ticket to return home, and I turned it in, got a ticket on a freighter, and took the press with me. That press is here at Crown Point now, though we have others we use more.

The press from Scotland in the Crown Point studio.

How did Crown Point Press begin?

In 1959, soon after I finished my schooling, I married Jeryl Parker, an artist whom I had met in London. We installed my press in the studio of an artist-friend, John Ihle, and lived in an apartment across the street. Our son Kevin was born in 1961. In 1962 Jeryl and I rented a storefront space in Richmond, an industrial town next to Berkeley, and lived in a little apartment in the back. We set up an etching workshop in the storefront; that year I got a business license for Crown Point Press. Jeryl was teaching at the College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, and I ran the shop. I didn’t publish at the time; a few local artists paid an hourly fee to work in the studio and have technical advice from me. I was also working as a typist for a company that supplied temporary services to banks and insurance companies.

In 1964, Jeryl and I separated and my grandmother helped me buy a house in Berkeley; it had a big basement for the press, and I could look after Kevin while I worked. I was able to hold classes in my basement studio for the University of California at Berkeley’s extension program, and I invited artists to do projects that I printed and Crown Point Press published. I also worked on my own art in the studio, and in 1964 published a bound book of my etchings accompanied by poetry by Judson Jerome, whom I had met in my college years.

Kathan in the Berkeley studio with her son, Kevin, 1965.

A friend suggested that Richard Diebenkorn might be interested in trying out the etching process. She said he liked using different kinds of mark making, and recommended me to him. He took plates to his studio, and when a painting would get “stuck,” as he said, he would copy the image onto a plate. It would be simplified and print backwards, and this was useful to him. He thought of etching as “a way of drawing.” Diebenkorn was the first artist (besides myself) that Crown Point published. Wayne Thiebaud, who at the time was showing in the San Francisco gallery that showed my own work, was the second.

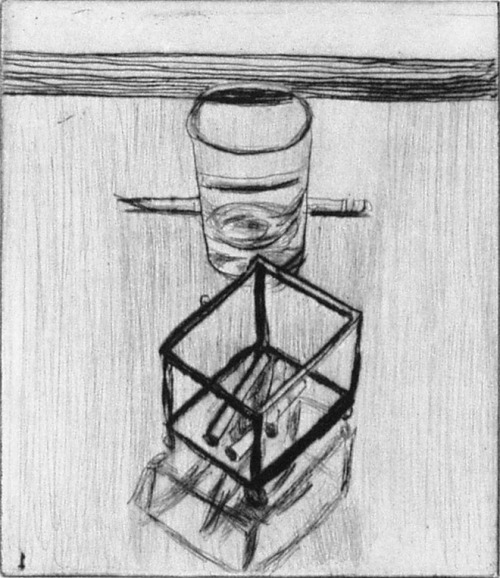

Richard Diebenkorn, #19, from 41 Etchings Drypoints, 1963, drypoint. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

How did your business grow over the years, from the single press in your home to the current size of Crown Point Press?

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, in addition to holding workshops and publishing and printing artists from California (Diebenkorn, Thiebaud, and Van Hoesen at first, then Bechtle, Tom Marioni, William T. Wiley, Robert Hudson, Chris Burden, Terry Fox), from Europe (Daniel Buren), and New York (John Cage, Joan Jonas, Pat Steir, Robert Barry, Hans Haacke). I also did quite a lot of printing for Parasol Press. Parasol sent New York artists to me: Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Robert Ryman, Mel Bochner, Dorothea Rockburne, Sylvia Plimack Mangold, and Robert Mangold. The owner of Parasol Press, Bob Feldman, was very supportive and showed me that it was possible to operate this kind of business.

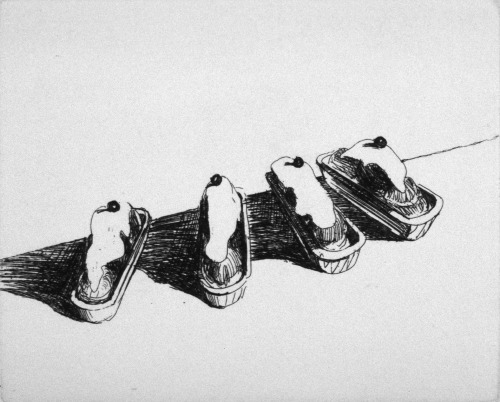

Wayne Thiebaud, Banana Splits, from Delights, 1964. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

What is the structure of the summer workshops at Crown Point?

We usually have ten people in one workshop with three printers. I start out with an introduction, basically outlining the concepts behind the process. Some of the people who attend have experience in the field, but some have never done etching before. Some are laymen in the art world; others are professional artists. Some teach printmaking. In the workshop everyone has a working space and people begin by getting a plate and starting to work. When they run into something they can’t figure out, they go to a printer, and the printer says “You need to use more of this, less of that,” or maybe they demonstrate: “Copy my gesture for wiping the plate.” That’s the way the workshops are run; they are very individual.

I generally poke around in the workshop, talk to people. I don’t actually do any work in the studio anymore, although I did everything there for a long time, and I understand what goes on there. All our Crown Point printers are really good, and they’ve got it figured out; they know exactly how to handle it all.

The workshops are only in summer, but all year long we have tours, lots of school tours and groups from out-of-town museums, so people can get a sense of what’s going on here. We also sell books about printmaking and art in general. We publish some of the books ourselves, usually when we think they wouldn’t exist otherwise.

The studio during a summer etching workshop, 2018. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

Have there been any developments in printmaking technology that you’ve used in your workshops?

We pretty much do it the same way Rembrandt and Goya did, except with more color. Not much has changed from back when they did it; I think that’s one of the interesting parts. A lot of the process involves using materials and techniques an artist may not use regularly, such as drawing on copper plates using tar, wax, salt, and sugar syrup. It’s all hand done and the materials are so tactile and beautiful.

Tom Marioni creating the etching, The Sun’s Reception, Sausalito, CA, 1974. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

How have you balanced the workshops with the operation of the gallery business?

In 1988, I moved Crown Point Press from Oakland to San Francisco, and Valerie Wade joined us. Her title now is Director/Partner. She handles the gallery side of the business, attending art fairs and developing our network as well as planning and hanging our shows. She and I also discuss which artists to invite to create prints here.

How do you choose the artists you invite?

That is the single most-asked question I get at Crown Point, and I am still unsure how to answer it. Valerie and I are glad to have recommendations from artists who have already worked here, and she is in touch with the art world in general through her attendance at art fairs and her day-to-day networking. In our publishing program, we can only accommodate three, maybe four, artist projects in a year because the printing process is so time-consuming; if we are to stay in business, our published artists must already have developed markets. But, don’t forget, we also have summer workshops that anyone can join.

Which artists have worked with you recently, and who are you excited about now?

We’re always excited about the artists who work here, and we always have a great time with them. Charline von Heyl has been here fairly recently, and I like her, and her work, a lot. We had a wonderful show of new (and older) work by Darren Almond, who came from England, last fall. Mary Heilmann is very good. We showed her new color etchings last year. And we have a new project scheduled with Laura Owens, who is from Los Angeles and has worked with us before. Also, I’m hoping we might have a new project this year with Wayne Thiebaud, who was one of the first artists I worked with back in the 1960s; we have published his prints regularly over the years.

Charline von Heyl in the Crown Point studio, 2014. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

Can you tell us about the current show in the gallery?

The 2019 springtime exhibition at Crown Point Press focuses on a set of four recent etchings by Los Angeles artist Mary Weatherford. She is known for attaching lighted neon tubes to the surfaces of her paintings; the prints, without neon, have a strong interior light. “Gesture,” the accompanying group exhibition, reaches back into Crown Point’s history to Brice Marden’s “Five Plates” of 1973, and includes later work by Pat Steir, Mary Heilmann, Amy Sillman, Charline von Heyl, Jacqueline Humphries, and John Zurier. In June and July we’re featuring a bound book of etchings about California by Fred Martin titled “Beulah Land.” Crown Point published it in 1968; this show is part of a citywide celebration of The Dilexi Gallery, which was an important influence in San Francisco’s art history.

Installation view of “Mary Weatherford,” 2019. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

Do you have any advice for collectors who want to learn more about print as a medium?

I think people are rewarded by close looking. These prints have dimension; it might seem, at first, like they’re printed on a flat sheet of paper, but they are actually embossed into it. This is the only print process that does that; in lithography, woodcut, silkscreen, the ink sits on top.

Etchings have a special energy when you look at them closely. I think that when people are able to see this, a light comes on inside and they think, “oh, this is really something different.” And then the door is open to a real appreciation of the process. We aren’t just making a drawing on a plate, putting some ink on it, and printing it. It’s much more complex, and although the artist has technical help from our printers, everything is in the artist’s control completely.

If you can visit us in San Francisco, you will be welcome; we give tours that include the studio. (If an artist is working in there, we have a secondary studio you can see.) Some of the people who take our summer workshops are collectors. Some are artists, but we also get people who come in and say, “I’m not an artist, or a collector, but I want to find out how it’s done.” This curiosity is always rewarded. No matter how the drawing starts out, when it’s printed, it looks purposeful, because the printing, in itself, provides a kind of presence.

Installation view of “Green by Richard Diebenkorn: The Story of a Print,” 2017. Courtesy Crown Point Press, San Francisco.

Do you have some advice for somebody thinking of opening a gallery right now?

It’s important to establish a close connection to the artists in your network. We learn about interesting artists through word of mouth from the artists we already work with. You also should be ready to pounce on something new as soon as you can. My partnership with Valerie Wade has been essential, as she’s really out in the world and can get a sense of what’s going on and which artists might be ready for a project with us.

Looking back, I’m astonished by some of the things Crown Point Press has done. We’ve printed and published a lot of great art, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D. C. and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco both have archives of our work. We are lucky to have had a lot of goodwill over the years. Some of the workshop people and printers who have worked here have opened their own workshops. The artists who work with us generally become engaged with what we are doing and often return for another project. We publish books on the etching processes so everyone can learn, and we hope more artists and more printers will become interested in using this medium. The technology is very old, and I think people appreciate the fact that we’re helping to keep it alive.

6 years ago

6 years ago